These fragments I have shored against my ruins —T S Eliot I will open my mouth in parables, I will utter things hidden from the foundation of the world. —Matt. 13:35

What follows is an exercise, the sort of prognostication science-fiction writers use in their craft; or in other words, a much exaggerated picture of a possible future…

The human population has collapsed and the Christian religion has been lost. Or, if not entirely lost, it remains only in fugitive, degenerate pockets. These groups lack the intellectual heritage of the churches: all that has been obliterated. Doesn’t matter how, but let’s suppose everything considered worth keeping was digitized, and then the people who control the databanks… This being the case, whatever rites these “Christians” perform bear little resemblance to those performed today, and whatever meaning is left in them is largely inscrutable even to the practitioners themselves.

But we must be more thorough than this. Imagine that anything we might call "classical theism" or metaphysics has also been lost. Most of humanity in this grim future world are actually not human anymore. They are transhuman, much like the civilization in Brave New World except, I shall speculate, artificially androgynous. They don’t gestate new (trans)humans in the womb (they’re sterile, though this fact is irrelevant since they wouldn’t want to bear children anyway) but in “incubators” which are cloned (old-style) human females. We are already willing to contemplate, and are apparently rapidly approaching the capability to do such a thing. The bulk if not the entirety of the arts and culture of human history can have little meaning to such a people, so why would they preserve any of it? Meanwhile the old-style humans eke out a raw and primitive existence in the shattered biosphere that lies beyond the walls of the terraforming cities and plantations of the transhumans.

This is all basic scifi dystopian stuff—I’m not being original. The point is that even if someone—a human—were to stumble upon a copy of, say, Heidegger or Nietzsche, it wouldn't make sense because the Christianity or the "onto-theology" those guys rail against is just gone. But not just Christianity and its civilization. In fact, the whole intellectual and artistic heritage of humankind over the past 2500 years, the ‘Axial Age’ and its descendant cultures visible in literary artifacts ranging from The Book of Changes to The Book of Disquiet and beyond—all of that is gone. That is, until one day…

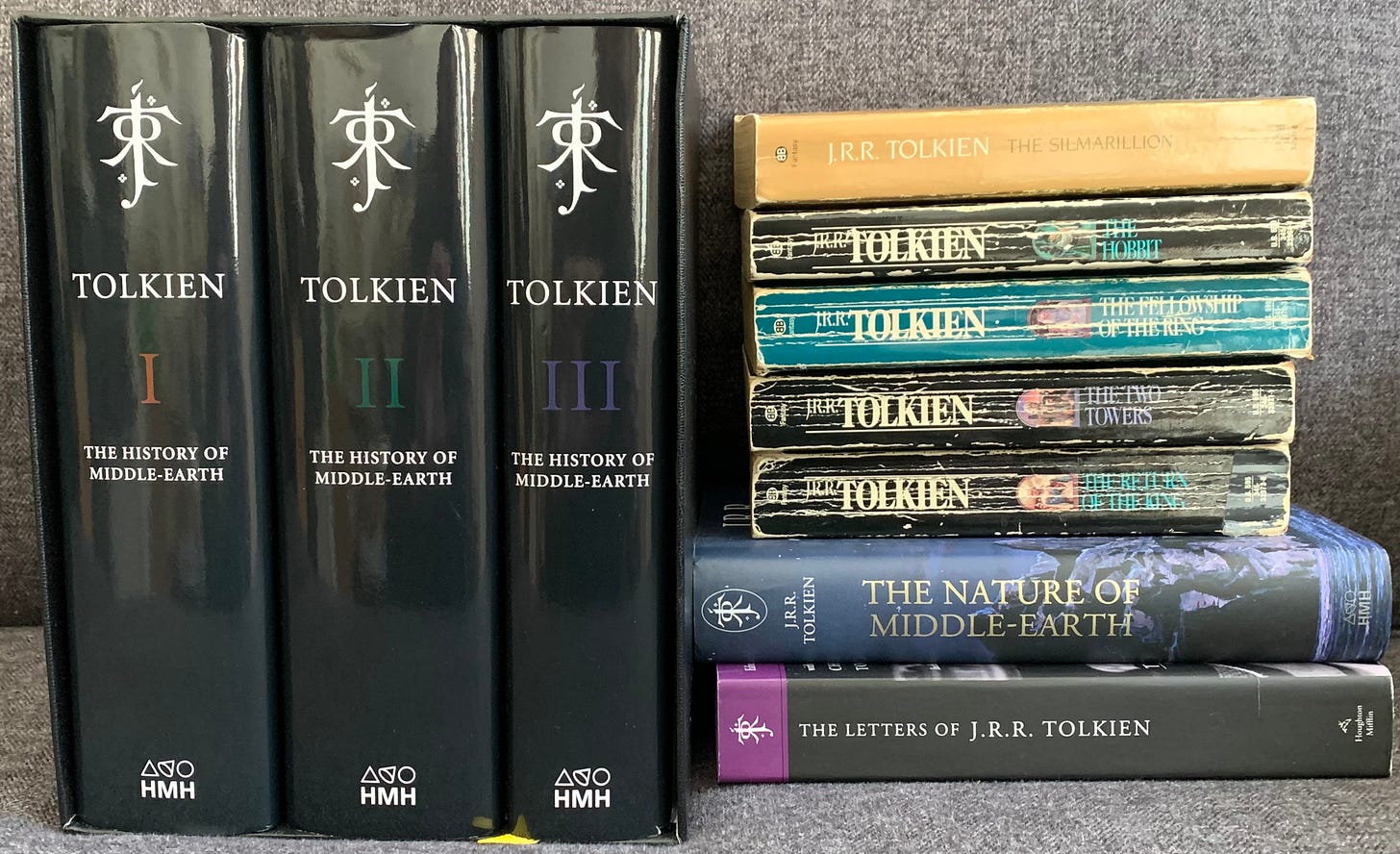

Tolkien returns. Somehow, out of the wreckage of whatever final apocalyptic struggle divided Earth into human and transhuman zones, someone, whether by chance or by heroic undertaking, retrieves a few tattered copies of John Ronald Reuel Tolkien’s complete writing. This is where the thought experiment really begins: What sort of culture will the scattered bands of old-style humans be able to construct based on Tolkien’s works? First of all, are the texts rich enough to serve as such a foundation?—At once foundation and the pitiful fragment remaining of Western Civilization at its most integral, complex and mature, which we must remember itself has at its core just the Hebrew Scriptures combined with a handful of texts from ancient Greece.

Would anything like Western Civ, with its contradictory tendencies toward empirical, abstract, and symbolical modes of thought, arise again from Tolkien’s work? Could we be more specific and imagine a new version of Hellenized Jewish-Christian religion—let’s give that the technical name messianic transcendental monotheism—built on the Tolkien Canon? Supposing we answer yes to these questions, could we assume that since the actual Western Civ is at present engaged in a complex process of self-deconstruction, would the same fate come to Western Civ 2.0 founded on Tolkien?… All of this has happened before, and it will all happen again. (That’s J M Barrie, author of Peter Pan, and I believe the line was used in Battlestar Galactica as well.)

I am of course being fanciful and reductive. That’s how thought experiments work, by a kind of reductio ad absurdam. I undertake the experiment in order to think about what lies at the core of civilization or human society, and also to think about a particular modern literary genre which, contrary to popular opinion, I don’t think Tolkien founded so much as consummated. I don’t think there will ever be another fantasy like Tolkien’s Legendarium. In a way, the Legendarium transcends the genre Tolkien is often said to have founded, and it may be that we err in thinking of him as a fantasist, even the best of all fantasists.

Why might this be so? One way to think about it is to ask what other works or what other author would be as good a contender for civilization-founding? I know people who would say (or wish to say) Dante. But Dante is useless without a massive critical apparatus. More important, I think, is the fact that La Vita Nuova does not stand in relation to La Comedia as The Hobbit stands to The Lord of the Rings. What I mean is best illustrated, I think, by the fact that while Dante may have been nine when he first glimpsed Beatrice Portinari, no nine-year-old is going to be swept into a world of imagination by reading La Vita Nuova; whereas a great many nine-year-olds have been transported by The Hobbit. In fact children can get a lot out of some Dante, though I would argue there is an enormous amount in even Dante’s simpler texts they cannot grasp. But in a mysterious and subconscious way I think children can get all of what’s in everything Tolkien wrote.

Only two other authors come to mind in this strange experiment: Blake and Goethe. But I think they both fail the children test, which is the crucial test. Whosoever shall not receive the kingdom of God as a little child, shall not enter into it… There is a simplicity, maybe a naiveté in the Legendarium, despite its richness. It cuts to the quick, and although you cannot learn how to farm or even how to wield a sword effectively from reading Tolkien, you can learn from his works how to be an embodied, intelligent, mortal being living in a society possessing sacred history and organized around a mythos. And here’s the thing—the Legendarium does that without any interpretive notes. You could get the same thing out of ancient epic, but not without notes. You need someone to tell you, “In ancient Greece they believed this and that about the gods…” “The reason Aeneas is called pious all the time is because the ancient Romans valued…” Tolkien’s work is self-contained without being “private,” as for example scholars say of Blake’s.

That is a lot—though I hasten to clarify it doesn’t mean a literate adult should prefer Tolkien to Dante or Blake or whoever—but is it enough? If you had to rebuild civilization would you want to add to the Legendarium another text? In China there developed over time the idea of the three teachings, i.e. Taoism, Confucianism and Buddhism. These three traditions, though they have grappled with each other at various times, ultimately can be said to rely upon each other and interpenetrate, creating a cultural complex which undergirds all of East Asian culture, not just Chinese. (Incidentally, this fact is why Westerners go astray when they appropriate only a single strand, e.g. Ezra Pound’s focus on Confucianism or modern bourgeois adapting Buddhism to Western individualism and its various un-Buddhist projects of liberation or salvation.) The Chinese have thought about their culture for a long time, and in so doing have identified various groupings of “classics,” which suggests that no one body of lore alone suffices. What is in Tolkien’s work, and what is missing from it?

First let me show something of utmost importance that Tolkien’s work does possess, though he gets too little credit for it. One of the chief reasons I hit upon Tolkien as a likely foundation is precisely the way so many fragments cohere in his work. He was, as Tom Shippey has persuasively though not exhaustively argued, a distinctly modern author, albeit one who was more able than any other to delve into past epochs for his inspiration and materials. And the chief boon modernness brought to Tolkien, or one of the most vital ‘fragments,’ was a sensitivity to the natural world he was able to articulate in his writing. There are a great many places in his most popular works where this penchant is on display, but I would like to quote from the poetry, the better to display the juxtaposition of an archaic style—Tolkien developed a prosody based heavily on that of Old English—with what I cannot emphasize enough is a modern sensibility not so much in terms of the natural world itself—in fact, as we’ll see, the attitude to nature is atavistic—but regarding the place of the natural world in literary writing: it is to be an essential element and not merely an ornamental feature.

The following passage comes from The Fall of Arthur, the long poem on the eponymous theme that Tolkien abandoned at an unknown date. Here Arthur’s army is advancing into the pagan east of Europe in a preemptive campaign, after so long fending off these same foes from the shores of Britain. This is a virtuosic passage, and though the language is deliberately archaic in a way comparable to many other writers on this and related themes, nothing remotely like such extensive and intensive landscape description may be found in premodern literature.

Foes before them, flames behind them, ever east and onward eager rode they, and folk fled them as the face of God, till earth was empty, and no eyes saw them, and no ears heard them in the endless hills, save bird or beast baleful haunting the lonely lands. Thus at last came they to Mirkwood's margin under mountain shadows: waste was behind them, walls before them; on the houseless hills ever higher mounting vast, unvanquished, lay the veiled forest. Dark and dreary were the deep valleys, where limbs gigantic of lowering trees in endless aisles were arched o'er rivers flowing down afar from fells of ice. Among ruinous rocks ravens croaking eagles answered in the air wheeling; wolves were howling on the wood's border. Cold blew the wind, keen and wintry, in rising wrath from the rolling forest among roaring leaves. Rain came darkly, and the sun was swallowed in sudden tempest.... There evening came with misty moon moving slowly through the wind-wreckage in the wide heavens, where strands of storm among the stars wandered. Fires were flickering, frail tongues of gold under hoary hills. In the huge twilight gleamed ghostly-pale, on the ground rising like elvish growths in autumn grass in some hollow of the hills hid from mortals, the tents of Arthur. Time wore onward. Day came darkly, dusky twilight over gloomy heights glimmering sunless; in the weeping air the wind perished. Dead silence fell. Out of deep valleys fogs unfurling floated upward; dim vapours drowned, dank and formless, the hill sunder heaven, the hollow places in a fathomless sea foundered sunken. Trees looming forth with twisted arms, like weeds under water where no wave moveth, out of mist menaced man forwandered. Cold touched the hearts of the host encamped on Mirkwood's margin at the mountain-roots. They felt the forest thought the fogs veiled it; their fires fainted. Fear clutched their souls, waiting watchful in a world of shadow for woe they knew not, no word speaking.

One of the reasons I so value Tolkien’s articulation of the natural world throughout his work is that it stresses a point which is far too often neglected by those who talk about “re-enchantment,” namely that any enchanted cosmos worth the name has good as well as bad enchantment in it, good as well as bad fantasy, horror as well as theophany. That, at least, is what every traditional culture has intuited, and it is why I say the attitude to nature on display in a passage like this is atavistic, even though from a formal point of view it is a novelty to include such a passage. Nature in this old view, as the Ents of Fangorn Forest put it, is not on anyone’s side, because no one is on Nature’s side. In a passage like the one above, you get a deep impression of the primeval Hercynian Forest of northern Europe, such as perhaps the Roman legions experienced it in their campaigns against the Germanic tribes, and Tolkien draws from such an aesthetic the Mirkwood and Fangorn of his Middle Earth.

Of course, Tolkien could imagine a beautifully enchanted forest as well, Lothlorien. All of this draws upon very ancient roots indeed. It is the stuff of animistic, pre-Axial (i.e. pre-metaphysical) religion. You can see it in the creation myth of Ainulindalë, in which the Valar and Maiar mix with the elements of Arda, and you can see it as well in strange, inexplicable figures who seem to have intruded into the Legendarium from Earth’s own deep past, like Tom Bombadil. No wonder that in the essay “Walking” Thoreau wrote:

I walk out into a Nature such as the old prophets and poets, Menu, Moses, Homer, Chaucer, walked in. You may name it America but it is not America: neither Americus Vespucius nor Columbus nor the rest were the discoverers of it. There is a truer account of it in mythology than in any history of America, so called, that I have seen.

It is almost as if Thoreau foresaw Tolkien, or mythology made new. Ever since the literature of North America became a self-conscious project (arguably around Thoreau’s time or a little earlier, though some might push the date back much earlier) it has sought to differentiate itself from its European parent. This has proved difficult for even as stubbornly individual a writer as Thoreau. Nevertheless, I wonder if Thoreau is the author I would pick to complement Tolkien in the work of refounding—civilization? It is an odd word, after all, to use in conjunction with Thoreau’s work and with that of the man who described himself as something of an anarchist and was profoundly skeptical of the machine age. So perhaps in the thought experiment we should be thinking of refounding not civilization but a culture worthy of the name.

I had originally thought this series of essays on a new literary transcendentalism would come in three parts, but I see now there will be four. In the next letter I will conclude the juxtaposition of Thoreau with Tolkien.

Jonathan, I've been following this conversation with interest & delight: thank you for it. I am on the alert everywhere for signs of reemerging transcendence in literature right now & am eagerly awaiting the connections you'll make next!

Yes, even the unserious is covertly dangerous, and much of what appears a lark is more foreboding. I remember decades ago when one of the "superstations" was showing the Hayley Mills comedy, The Trouble with Angels, which is a relatively anodyne film about a mischievous youth in a girl's school run by nuns. The unexpected turn is when the heroine is surprised by the lure of vocation. It's sweet and strangely powerful, but the marketing wing of the station had intros to the movie with zany, psychedelic graphics proclaiming the entire work "Weird." Fast forward thirty years and a satanic ritual on network tv is greeted by a CBS tweet that "we are ready to worship." (They have since erased the enthusiastic servility to the diabolic.) The power of words and image, the nature of fiction as enacting strategic moves of spiritual kingdoms, none of that is conceived by folks who are basically an incoherent fusion of positivist nihilism and ideological ersatz religions with their own tests for orthodoxy and intolerance for the heretical. But you know if you say these things, one will be quickly dismissed as a fundamentalist who is opposed to Halloween and Harry Potter. The sage wisdom needed to discern entirely escapes contemporary mores.